Saturn was Transiting His Sun at the Time

William Blake, long considered one of England’s greatest poets and artists, had exactly one public exhibition of his art. It was held at his brother’s haberdashery shop in 1809. An editor of a local periodical and his brother showed up and wrote a memorable review. They evidently felt the need to speak out “when the ebullitions of a distempered brain are mistaken for sallies of genius…Such is the case with the productions and admirers of William Blake, an unfortunate lunatic, whose personal inoffensiveness secures him from confinement.” The accompanying catalogue was “a farrago of nonsense, unintelligibleness, and egregious vanity, the wild effusions of a distempered brain.” His exhibition of course made Blake no money, reinforcing his desire to continue with his life work as he perceived it. The Hunt brothers may have inadvertently done succeeding generations a favor.

William Blake (1757-1827)

Their review does give us important information. We know Blake and his work had some admirers; we also know that Blake’s behavior was not that of a lunatic but that he was “inoffensive”. We also know that conventional literary people would find his writings largely incomprehensible. We can talk about the Hunt brothers being “muggles” but they are likely representative of many of Blake’s contemporaries. “Egregious vanity” is an attribute that accompanies many a prophet, real or self-proclaimed.

Less than thirty copies of Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience were published during his lifetime and only some copies of his later work, including his late prophetic epics, were distributed. He and his wife fought off poverty during their lifetimes, and it was only decades after William Blake’s death, due to the efforts of one Alexander Gilchrist, that his reputation entered the top tier of English poets and artists. Although too often associated with our culturally licentious 1960’s, interest in Blake and his work has continued to this day.

Was William Blake crazy? If he walked into a modern psychiatry office he might have left with a diagnosis. He saw and talked to angels and spirits from about the age of four; in conversation and in his writings, he often spoke of visions and of having conversations with the objects of these visions. He seems also to have been saddled with clinical depression at various times of his life. From an early age, Blake disliked rules and restraints and was thankfully kept from public school. He wrote once, Thank God I never was sent to school/To be flogged into following the style of a fool.” Oppositional defiant disorder? (This little couplet is from Leo Damrosch’s Eternity’s Sunrise: The Imaginative World of William Blake. The book is a good read and has been a resource for this profile.)

Despite suspicion – or allegation – that Blake was crazy, he appeared to have a solid marriage and lasting friendships, a strong sense of the suffering of others, and a full share of wisdom. Damrosch quotes a minister of Blake’s acquaintance who, when asked if the artist was “cracked”, replied, “Yes, but his is a crack that lets in the light.”

You Know Him At Least a Little

I’m sure you’ll recognize these lines below, they show Blake’s activity of mythologizing his world, of seeking to reconcile the sacred with the ordinary.

Walk upon England’s mountain green:

And did the holy lamb of God,

On England’s pleasant pastures seen!

And so on, and it’s likely you’re familiar with its musical setting and may be feeling a bit nauseated, especially if you’re from the U.K. This poem, usually called “Jerusalem” is part of the preface of his late prophetic work Milton. Here, as with John Lennon’s “Imagine”, people get dewy-eyed without realizing that this song, like Lennon’s, is delightfully subversive.

For me the following lines, never published in his lifetime, appealed to me when I was young. “Auguries of Innocence” is a string of couplets that gets darker as the poem continues. Surely it made your acquaintance at some time.

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower:

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour.

A robin Red breast in a Cage

Puts all Heaven in a Rage.

A dove house fill’d with doves and

Pigeons Shudders Hell thro’ all its regions….

Here’s a little more. Blake is protesting the reductive rationalism that went along with the so-called Enlightenment of the eighteenth century. Blake contrasts the tendency to atomize reality with a larger vision of the spiritual imagination. When I was in college this was a favorite of mine.

Mock on, mock on, Voltaire, Rousseau;

Mock on, mock on; ’tis all in vain!

You throw the sand against the wind,

And the wind blows it back again.

And every sand becomes a gem

Reflected in the beams divine;

Blown back they blind the mocking eye,

But still in Israel’s paths they shine.

The Atoms of Democritus

And Newton’s Particles of Light

Are sands upon the Red Sea shore,

Where Israel’s tents do shine so bright.

Here are illustrations of two famous poems from Songs of Innocence and Experience. Blake saw visual setting and a poem’s words and rhythms as one thing.

Maybe you’re familiar with the poem “Tyger, Tyger” or “The Chimney Sweeper” from his early Songs of Innocence and Experience. The first poem, metered like a beating heart, shows a mystic reverence for the uninhibited live force. The latter exposes Blake as an ironist, a fierce social critic in early industrial-revolution London, and one who calls out established religion in its role as protector and propagator of social oppression. After the disappointment of the French Revolution, Blake understood that true revolution is creative and from the inside-out, integrating the person, bringing together the finite and the infinite, our measurable time and eternity.

Here is the first half of his famous poem “London”, also an early work. It illustrates his power of observation, and an eye of compassion. Just let your mind dwell on the final line here — the poem continues for two more stanzas.

Near where the charter’d Thames does flow.

And mark in every face I meet

Marks of weakness, marks of woe.

In every cry of every Man,

In ever Infant’s cry of fear,

In every voice, in every ban,

The mind-forg’d manacles I hear…

One should not confuse Blake with a social revolutionary, for he led the life of an artist, not an activist, and his focus was on creative transformation of the culture and the individual together. It was the mind of the oppressed that insured the continuity of oppression: can our minds change?

Many of Blake’s aphorisms are well-known, especially to those with at least a passing interest in hallucinogens, like Aldous Huxley and Jim Morrison, and some of us at one time or another.

For man has closed himself up, till he sees all tings thro’ narrow chinks of his cavern.

Surveying this abundance, we must note that Blake’s poetry is one-half of his output, since we must include his copious production of visual art. His skill at engraving, etching, and printing allowed him to receive some income illustrating others’ works but he also applied engraving and water colors to illuminate his own texts. It has been argued that Blake is the greatest visual artist that has emerged from England but I will leave that discussion to others.

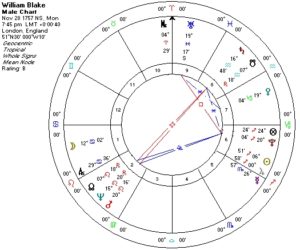

Arriving at the astrology of William Blake’s returns me to a chart I used to illustrate some ancient astrological techniques ten years ago in Astrological Roots: The Hellenistic Legacy. The astrology of his chart and his life, like his art and poetry, has often returned to me over the years.

William Blake and Whole Sign Houses

An Ascendant attwenty-nine degrees of a sign often distresses people early in their use of Whole Sign Houses. This system of houses is based on the relationship of all positions to the zodiacal sign of the Ascendant, whether the Ascendant has just entered or is about to leave a particular sign. Consequently, the birth time is off by even a minute when an Ascendant is very early or very late in a sign, every house position can change. I have been using Whole Sign Houses for almost twenty years and I have recovered from this anxiety but it took some time.

Whole Sign Houses give Blake’s Moon not in the hidden Twelfth House but the strong and visible First. Additionally, the Moon’s condition of sect is very strong – the chart is nocturnal, Moon is on the other side of the Ascendant than the Sun, and it is in the “feminine” watery sign Cancer. Perhaps I have already hinted at an interpretation: Blake was a very sensitive person with strong emotional connections to those close to him, those further away who are subject to suffering, and even those in invisible realms. He had strong visceral, emotional, and intellectual antennae. His poem “London” portrays him as walking around the city soaking in the life stories and suffering of those he sees. A planet in a sign of dignity can characterize the individual as confident about the activities of the planet involved and Blake’s lunar responses appear to be strong, confident, and right on the surface. I see nothing “stiff upper lip” about this man. His sensitivity contributes greatly to his excellence as a poet and artist.

Some astrologers think that the system of Whole Sign Houses is a relic of some primitive simplicity of the astrology of days gone by. Mr. Blake’s chart provides a wonderful counterexample to this, for the Ascendant degree reveals an important connection to Jupiter; the degrees of their respective positions are symmetrical to the Aries Point, they are contra-antiscia. William Blake’s Ascendant degree – his personality, his interaction with the world, his life energy – strongly connects with Jupiter, the planet of inclusion and integration with larger fields of experience.

Ah, Jupiter!

Blake did write that “the road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom” and to some astrologers that sounds like Jupiter. Those who have rendered Jupiter, the Greater Benefic, into a planet of everything overdone, and might point to the seeming unrestraint of Blake’s prophetic books to support that contention. I read his prophetic books differently and instead look at Blake as an immensely gifted person whose values leaned toward the “big picture”, who saw the particular as cosmic, and who would challenge his culture and his readers into a greater wisdom born from imagination.

One of Blake’s best-known illustrations, the limited deity measuring out the world. Note the cramped posture of the deity, even if surrounded by light.

Aside from its connection to the degree of the Ascendant and being in its own sign Sagittarius, how is Blake’s Jupiter so important? It is in the weak Sixth House and is under the Sun’s beams. The latter factor is disqualified since Jupiter is in its own sign, triplicity and even Egyptian terms. Placement in the Sixth House often means difficulty personally benefiting, having the planet do good work for you. As we have noted, Blake’s Jupiter didn’t exactly bring him fame and profit.

Jupiter is also the dispositor of the Lot of Fortune and the Sun. Adding to Jupiter’s proprietorship over these places, Sun and Fortuna are all in Jupiter’s triplicity since Blake’s chart is nocturnal.

The Lot of Spirit, symmetrical from the Ascendant to the Lot of Fortune, signifies how we make personal choices, how we are driven by our motivations, how we will try to impact the world with ourselves. Blake’s Lot of Spirit is in the Ninth House in Pisces and is governed by Jupiter that, along with the Sun, is in the tenth sign from the Lot! Blake will, to the greatest extent possible, pursue his own ideas and go his own way in life, and the character of this self-determined journey will be of the nature of Jupiter.

We get further testimony from the Hellenistic Lot of Courage that is in Aries, his Tenth House of career or livelihood. In his nocturnal chart, this Lot is drawn from the distance between the Lot of Spirit and Jupiter , the number of degrees then cast from the Ascendant. Thus further articulates the importance of the Spirit-Jupiter connection for Blake.

Venus, Sexuality and Art

Moon’s application is to the other angular planet, Venus in Capricorn. This gives a different message from what we have seen so far.

Catherine Blake (1782-1827)

We begin with his marriage to Catherine at an early age. They would stay married all his life. As with many women at that time and of her class, she was illiterate when they were married. William taught Catherine to read and write and she became an indispensable companion and co-worker of his many projects. Yes, his household revolved around his creative projects, not much else. Although William was critical of marriage as an institution and considered monogamy unnatural, he and she seemed to have been devoted to each other throughout their lives. William felt genuinely guilty that he was not a better provider for Catherine. As Venus is in the Seventh House of marriage, all this conforms nicely to its placement in saturnine Capricorn.

Blake portrays sexuality in different ways throughout his works. Anticipating Freud and others much later, Blake made much of the negative effects of repressed instincts, especially those of a sexual nature. He was frequently misread as more libertine than he was – the natural world of sexuality, he felt, was part of the “World of Generation” that reduced the freedom and inherent divinity of humankind. His work also showed a strong awareness of sexuality in the context of individual and social dominance. Do we see here, alongside Venus in Capricorn, Mars in Leo conjunct Neptune and opposing Saturn? I will say more about this combination below.

From his illustrations of Dante, meeting Beatrice a the top of Purgatory. Note Beatrice’s translucent and revealing attire.

Blake greatly admired Michelangelo’s artistic clarity and emphasis on the human form and he especially admired Durer’s engravings. Blake’s visual artistry shows clearness of line and form within a highly symbolic structure that connects to his lifelong interest in medieval art. Blake’s artistic style is part symbolist, part classicist, and part romantic. This makes his art, as with his poetry, individual and difficult to classify, similar to Moon in Cancer opposing Venus in Capricorn. Blake had no interest in the artistic work of his more successful contemporaries – pretty landscapes and portraits of the wealthy and well-connected.

Happily, as a youngster William’s merchant father did not send him to school but to be apprenticed to an engraver. In this way, William had a vehicle for his creativity and a way to make a living. As an adult, Blake owned a large printer – his home was his workshop and his wife was his co-worker. He developed styles of engraving, etching, and printing to combine poetic text with illustration. Publishing all his own works by himself gave him expressive freedom and required technical exactitude and great physical exertion. Notice that earthly Venus in Capricorn is in close sextile from Uranus, the planet of the individual and innovative – this manifested for him in artistic pr0cess and technique as well as content.

Mercury, Mars, and their Friends

We now arrive at those planets best viewed in combination. Happily using only traditional “Ptolemaic” aspects– since yods don’t exist — the job is simpler than it could be.

Mercury is an important planet for any poet, and its prominence begins with its close trine to the degree of the Ascendant and being in the strong Fifth House. In the fixed sign Scorpio, Mercury is governed by Mars, in square to Mercury and in the fixed sign Leo.

We first note the prominence of his strongly-expressed “message” in his artistic work. Unlike some other great poets for whom content is secondary to poetic style and the use of words, Blake’s poetry and art emphasized content, placing him in line with other “prophetic” poets in English like the “metaphysical poets” and John Milton earlier in the seventeenth century, Walt Whitman in the nineteenth, and T.S Eliot in the twentieth.

We first note the prominence of his strongly-expressed “message” in his artistic work. Unlike some other great poets for whom content is secondary to poetic style and the use of words, Blake’s poetry and art emphasized content, placing him in line with other “prophetic” poets in English like the “metaphysical poets” and John Milton earlier in the seventeenth century, Walt Whitman in the nineteenth, and T.S Eliot in the twentieth.

Blake’s Mars increases in importance with its relationship to Mercury. As the planetary dispositor of Mercury and Moon, Mars is, according to Ptolemy, the planet that governs his soul. Mars is also the ruler of Aries the sign of his Tenth House of career. This may manifest in the physicality of his work and its crusading character. Recall the last stanza of his famous “Jerusalem” in which he casts himself as an intellectual warrior, fighting the “mental fight” for the sake of personal and world transformation. Although occasionally Blake would write and draw out of creative expression for its own sake, mostly there was a point of view he wished to express through his art.

The Mars-like nature of Blake is further supported by the role of fixed stars in his chart – his Sun is conjunct Antares, the “heart of the Scorpion,” of the nature of both Mars and Jupiter. Mars itself co-rises with Sirius, a star that, at its best, displays both energy and brilliance.

William Blake’s Mars has the complication of being aspected by two planets antithetical to its nature, Neptune in conjunction and Saturn in opposition. Neptune can be a dissolving and weakening influence on Mars, or can bring a spiritual or sublime dimension into Mars’ natural machismo. Blake appeared to have left his anger and outrage on the printed page. There was one incident where an altercation with a trespassing soldier resulted in Blake being accused of speaking against the king. Blake was found not guilty but this appears to have been a traumatic event for the artist.

Saturn can be a restraining or condensing influence on Mars, and Blake’s life and work show us both influences of Saturn. We’ve already noted the disciplined physical exertion that accompanied his work. Part of the genius of his Songs of Innocence and Experience is the complexity hidden by the deceptive simplicity of children’s songs. Another saturnine effect was Blake’s ability to live with fewer financial resources and less comfort than he would like. Saturn, in combination with Mars, can bring austerity into one’s life, willingly or not.

Noting that in a nocturnal chart Mars is in sect and Saturn is not, we may arrive at Blake’s tendency toward despondency and depression – especially if Neptune is also part of the mix.

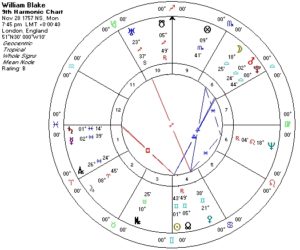

Visions, Prophecy, and the Ninth Harmonic

Blake’s poetic works roughly divide into two large segments: the condensed but accessible poems of his early work, especially his Songs of Innocence and Experience, and the much more difficult “prophetic” works. In these larger works, he developed his own mythology that has a Biblical not Olympian tone, wrote much in the style of the prophets of the Hebrew Bible. These works contain passages of brilliance alongside material that seems just weird. Different from the critical reception of the catalogue that accompanied Blake’s public art exhibit, his prophetic writings are not unintelligible or the “wild effusions of a distempered brain” but contain a sophisticated open-ended mythic structure — and they’re not easy to read (modern scholarship helps mightily). I provide below a sample of the less compact poetry of his prophetical works.

The “prophetic” Blake was not attempting to read the future but to disclose through imaginative process our current worldly and cosmic situation, its causes, and the possibilities of healing and redemption. We meet Orc of the rebellious instinctual self, in contrast to Urizen, representing the fallen creative spirit shackled by logic, law, and the belief in an objective limiting reality; we meet Los, at whose forge genuine creation makes its beginning. And there’s Satan, representing the oppression of pure materiality, in contrast to Jesus, a being of divine love and compassion. There’s England but also Albion, the fallen England (standing for humanity as a whole), and of course Jerusalem, its possibility. There’s Golgonooza, a new city of art and the imagination built upon the ruins of London.

In this context and leaving traditional astrology behind, let’s feast on Blake’s Ninth Harmonic chart. A harmonic chart tunes the positions in a natal chart to a certain number. The Ninth Harmonic chart, repeating the zodiac every forty degrees (360 divided by 9) displays divisions of the number of personal and spiritual fulfillment (three times three, the trine being the nature of pleasure or worldly happiness). Often the effects of a prominent Ninth Harmonic chart can be seen in the areas of spiritual insight and creativity, with or without artistic expression. It seems that Blake’s large-scale prophetic works display much of what we find in this chart.

Note the prominent position of the Sun, the planet of authority, creativity, but also – at its best – higher consciousness. We’re not interested in sign and house position, only in the aspects between planets. We start with trines between the Sun and a Mars-Pluto conjunction that ponders the nature of mankind’s fall, its current displays of violence and oppression, and the possibilities of apocalyptic transformation. Sun has squares from a Mercury-Saturn conjunction, representing the strength of our “mind forg’d manacles” to quote an earlier poem – is this expression not a perfect rendition of Mercury and Saturn together, malignantly?

In the Ninth Harmonic chart the opposition between Moon and Venus becomes a trine with Neptune in sextile to both. Here the strong Neptune can give psychic abilities that can find creative or artistic expression.

Neptune acts in its visionary quality as a counterpoint to the expression of oppression and misery by Mars-Pluto in square to the Sun. The configuration with the Moon gives us sweetness alongside the stridency well-expressed by the configuration with the Sun.

A Parting Passage

John Milton returns from Heaven

I close with a passage from Blake’s Milton that depicts the great poet, at times indistinguishable from Blake himself, summoned from heaven in the grand enterprise of personal and universal renewal. Here, well into this poem, Blake gives us a conceptual vision, or is it a visionary concept, that brings together the universal, the cosmic, and the surface of the planet all woven together within an image like an hourglass with two inverted cones, one representing the infinite or eternal, the other representing the particular, somehow distinct and at one. We see not the compressed six or eight syllable lines of the Songs of Innocence and Experience but expanding ones of fourteen syllables or more that gives an entirely different expressive style.

Own Vortex; and when once a traveler thro’ Eternity

Has passed that Vortex, he perceives it roll backward behind

His path, into a globe itself infolding, like a sun,

Or like a moon, or like the universe of starry majesty,

While he keeps onwards in his wondrous journey on the earth;

Or like a human form, a friend with whom he lived benevolent.

As the eye of man both the east & west encompassing

Its vortex; and the north and south, with all their starry host:

Also the rising sun and setting moon he views surrounding

His corn fileds and his valleys of five hundred acres square;

Thus is the earth one infinite plane, and not as apparent

To the weak traveler confin’d beneath the moony shade;

Thus is the heaven a vortex passed already, the the earth

A vortex not yet pass’d by the traveler thro’ Eternity.

What does all this mean? It’s a viewpoint and also an invitation not to be a philosopher but a traveler, through earth and the infinite, through time and eternity. It is the act of imagination, not of logical intellect alone, that makes such traveling possible for us. In the words of Northrop Frye, one of Blake’s best-known commentators, “In Blake, we recover our original state, not by returning to it, but by recreating it. The act of creation, in its turn is not producing something out of nothing, but the act of setting free what we already possess.” (From “The Keys to the Gates”, 1966)

I know that the lord of the Soul is determined primarily by Moon and Mercury, but I don’t see the connection between the Moon and Mars. The article said that Mars was the dispositor of the Moon in Cancer. I assume you are getting this because the Moon is in the triplicity of Mars. And triplicity is sufficient? If I remember correctly, close aspects are taken into consideration also, so the opposition to Venus within 7 degrees is relevant too, but not strong enough to ‘outdo’ Mars?

thanks.

Gary, thanks for your feedback. I had meant that Mars was a dispositor — triplicity, as you point out — not the dispositor for Moon alone. I had meant that if you tally the dispositors for both Mercury and Moon then Mars comes out on top. I will change the ambiguity, thanks.