Of No Small Controversy

Moving from last month’s profile on Malcolm X, I continue to examine the lives of exemplary American social activists, now moving to women and their reproductive rights. The person most closely associated with this in the last century was Margaret Sanger, a lifelong advocate for “birth control” – her phrase – as a means to combat poverty and allow women their full potential as social and sexual beings. Over a hundred years ago and beginning in New York City, Sanger wrote and illegally distributed literature to women on methods of contraception, then illegally opened the first clinic for women seeking birth control option. Then she worked mightily to attract the medical community and the political establishment to her work, wrote and lectured worldwide for decades, helped form and presided over various organizations that culminated in the formation of Planned Parenthood that is today’s part of America’s social landscape.

Moving from last month’s profile on Malcolm X, I continue to examine the lives of exemplary American social activists, now moving to women and their reproductive rights. The person most closely associated with this in the last century was Margaret Sanger, a lifelong advocate for “birth control” – her phrase – as a means to combat poverty and allow women their full potential as social and sexual beings. Over a hundred years ago and beginning in New York City, Sanger wrote and illegally distributed literature to women on methods of contraception, then illegally opened the first clinic for women seeking birth control option. Then she worked mightily to attract the medical community and the political establishment to her work, wrote and lectured worldwide for decades, helped form and presided over various organizations that culminated in the formation of Planned Parenthood that is today’s part of America’s social landscape.

Social conservatives, past and present, have intensely disliked Margaret Sanger and Planned Parenthood and have succeeded in casting the latter as an abortion provider, although the services Planned Parenthood offers are far more extensive. To many their opposition seems another transparent attempt to limit government involvement to benefit women in poverty, and many others, who need assistance. This is likely to become an issue in 2018.

Only in the year before she died did the US Supreme Court rule against legal prohibitions on birth control; although Sanger had encouraged and helped support work toward the development of a birth control pill, it was only shortly before her death that one became available.

In a different era from our own, maybe I would not cite Sanger as “exemplary” – she could be difficult and unyielding, sometimes self-seeking, nor am I thrilled about the sacrifices those close to her were forced to make. Yet Sanger demonstrates how one can make a difference in our world: through a clear humanitarian vision that does not change, an ability to create and exploit opportunities that present themselves, and a flexible incremental approach that eventually wins the day. Surveying Sanger’s life will bring you face to face with some very difficult realities about America’s past that have, to some extent, continued to this day. (For a balanced and informative account of Margaret Sanger’s life, I recommend Ellen Chesler’s Woman of Valor: Margaret Sanger and the Birth Control Movement in America.)

Margaret Sanger’s legacy also faces the charge that she was racist, that she advocated population limitation to decrease the Negro population, that she was an advocate of forced sterilization, that she was an advocate for eugenics whose dark side would come to light in Hitler’s Germany. If you look through YouTube for biographical material on Sanger, you will find much from so-called conservatives side who link Sanger with eugenics and racism, nothing about Sanger’s role in the material and social progress of women worldwide over the past hundred years. Yes, she made some statements about eugenics and forced sterilization that make today’s sensibilities wince. There’s also context and the forgotten era in which she lived.

Sanger and Wonder Woman

William Marston and his creation. He was, we could say, intimate with Margaret Sanger’s family.

More felicitous, however, has been the renewed attention to Sanger in the context of last year’s film Wonder Woman. A few years ago Jill Lepore, an academic and writer for the New Yorker magazine, wrote about the creation of the character and comic book series in 1940. Lepore’s 2014 article, well worth reading, discusses the life and particularly the complicated home situation of William Moulton Marston, from which Wonder Woman was developed.

Marston was an experimental psychologist (credited with inventing the lie detector test) who advocated for women’s rights and sexual freedom.

Margaret Sanger as Wonder Woman: Note what she is jumping on

For many of his productive years he lived with his wife Elizabeth Holloway and a younger Olive Byrne in a sexually open arrangement, Marston fathering children from both women. Olive Byrne was the daughter of Ethel Byrne, sister to Margaret Sanger who has her own place in the history of the women’s movement. Although information is sparse, it’s clear that “Aunt Margaret” was an episodic visitor to the Marston/Holloway/Byrne household and they had sometimes visited her.

When Marston’s academic career fizzled, in part due to his unconventional living arrangement, he worked as a psychology consultant in Hollywood for a few years, and, based on an article by Holloway, was approached by the creator of “Superman” to help develop a female superhero. Lepore traced many of the incidentals of Wonder Woman to Olive Byrne, and one can trace features of the first story lines to the life of Margaret Sanger.

Natal Astrology and Personal Destiny

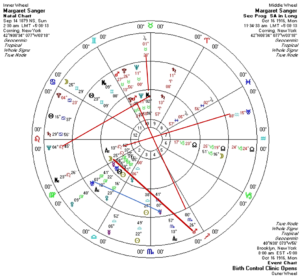

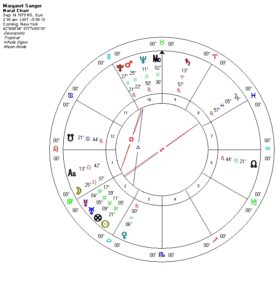

I am struck, as you will be, at the simplicity and transparency of Margaret Sanger’s astrological chart. Sanger seems born to do what she did in life. Dane Rudhyar wrote, and I agree, that an astrological chart manifests what the universe is seeking at the time of an individual’s birth and I can think of no better example than Ms. Sanger. For those familiar with the symbols and applications of astrology, analyzing her chart belabors the obvious.

Sanger was born at night, with Sun below the horizon, and therefore Moon is her “luminary of sect”, related to the Sun by rulership. Moon is in the all-important First House of one’s manifesting identity, one’s character. Generally, the Moon is that part of us that encounters changing needs and conditions through physical, emotional, and mental responses. The Moon is also associated with women, especially in their capacity to synchronize with life’s rhythms.

In the First House, the Moon can display strong sensitivity but, for Sanger, this would be in a more ostentatious Leo-like way. Her humanitarian vision of gender equality was based not on concept but strong personal feeling that she could express compellingly. As her fame increased she was called on to do public presentations; once she developed confidence she became a strong public speaker. She was also expert at tailoring her message to its audience: this is a lunar skill.

From the Moon one’s eye immediately goes up to the Tenth House of career where it finds Mars and Pluto in close conjunction. Moon is fifteen minutes of a degree from an exact square with Mars in Taurus. I’m less interested in Mars being in detriment in Taurus than it being in the fixed sign Taurus that bestows an aggressive nature that is also stubborn, persistent, and pragmatic, going along with Moon in fixed Leo. Had she Moon in Aries, her style would have been more of a bomb-thrower than one who will outlast the opposition through stubborn determination. Mars being fully in sect only increases its positive impact for Sanger.

Sanger’s Pluto mingles with Moon (square) and Mars (conjunction): her interest in birth control was not ideological but urgently personal, she showed a willingness to go the distance to advocate her position, and her work brought her face-to-face with the miserable conditions of immigrant women in the cities and many other women. Sanger addressed the underside of her culture’s institution of marriage that she often felt was often no more than socially-sanctioned sexual servitude for women. Yes, Pluto is a planet of intensity.

Virgo and Pisces

Sun in Virgo is the ruler of her Ascendant and dispositor of her Moon in Leo but also is in trine to Mars in Taurus. Virgo, as the mutable earth-element domicile of Mercury, is pragmatic and limits its scope so as not to overextend itself. Sanger kept the birth-control movement separate from that for woman’s suffrage. Although she stressed the particular difficulties of women in poverty, Sanger separated herself from her class-warfare-oriented leftist friends as she gained in fame and notoriety. Instead, she maintained a steady focus on her primary issue of birth control.

Now we arrive at Sanger’s other significant three-planet combination. Mercury in Virgo is conjunct Uranus and both planets oppose Jupiter in Pisces. This will tell us much about her mind and ideas.

Virgo is the feminine domicile of Mercury, not the conversation-starter-Mercury of Gemini but a problem-solver and engineer, someone who handles the details. Although out of sect in Sanger’s nocturnal chart, Mercury is outside the Sun’s beams, is swift of motion, and is the “oriental planet” to the Sun, the last planet rising visibly in the sky before the Sun rises. Overall it’s a well-placed planet and depicts a person not only intelligent but resourceful.

Mercury conjunct Uranus is the basic signature of the unconventional thinker and speaker – or maybe somebody who networks with strange people. Their placement in Virgo interests me greatly, for Virgo is not unconventional for its own sake but connects with concrete problems and concrete solutions.

Jupiter in Pisces, opposing Mercury and Uranus, is of another quality altogether: visionary but emotional and sympathetic, is prone to being right about the big picture but sometimes wrong on the details. Sanger attempted to find broad support for her advocacy of birth control and became involved in larger issues of overpopulation, eugenics, and, to a lesser extent, the sociology of sexual liberation. On none of these issues did she have as strong a voice, for at bottom she was not an intellectual or a conceptualizer; she was instead the nature of Mars with a good share of Virgo. Margaret Sanger was an advocate, an organizer and spokesperson, some who fought the good fight, not a public intellectual. This is not surprising, for Jupiter in Pisces is in the weak Eighth House and is wholly out of sect, Jupiter being a diurnal planet and Sanger’s being a nocturnal chart.

Saturn and Venus

Sanger’s Saturn is in fall in Aries and is also out of sect in Sanger’s nocturnal chart. Her persistence comes from the Moon-Mars-Pluto combination in fixed signs, not from Saturn. In a Tenth House square to her Lot of Spirit in Cancer, I suspect that Sanger had a melancholy side that may have dwelt alongside a temperamental nature. Saturn is also the ruler of the Seventh House of marriage and relationships, not a good indication for those who wanted to be or to stay married to her,

Venus is the ruler of her Tenth House and is in its own sign Libra. Venus is, of course, the traditional planet of sexuality and other fine things in life. Sanger’s intellectual development was facilitated by men she was romantically involved with: her left-wing husband, of course, but also Havelock Ellis. According to Ellen Chesler, after her marriage with William Sanger broke up there would be no one person with whom she could be with forever. Sanger did marry a second time, this being partly a marriage of convenience but also a happier alliance than her first. Although Sanger had different romantic involvements during her lifetime, including during her marriage, she was no “libertine”.

The Road to Brownsville: Earlier in Life

As with Malcolm X., Sanger’s early life became part of her “pitch”. She was the sixth of eleven surviving children and her mother is said to have had eighteen pregnancies. She was born Margaret Louise Higgins in upstate New York. Her father was a “free thinker” who eventually became a stone mason and was an activist for free education and women’s suffrage, and also liked the bottle too much. Margaret’s mother was more reliable and stable but died when Margaret was young, leaving her to help care for the home and younger siblings.

Margaret received some college education and at the age of 21 was a nursing assistant in White Plains NY. Two years later she married William Sanger, an architect and leftist, and they moved into the suburbs. Margaret the homemaker was restless living in suburbia.

New York and the Cause

After their house caught fire in 1910 and rebuilding it was not affordable, the couple went to New York City. Margaret began working as a visiting nurse in the impoverished immigrant communities in Manhattan’s Lower East Side. She encountered the heavy toll uncontrolled pregnancies exacted on these families, and the dangerous (and often lethal) means whereby women endeavored to terminate unwanted pregnancies. Sanger’s leftist tendencies brought her into political activism alongside Upton Sinclair, John Reed, and Emma Goldman.

However, Sanger’s message was along feminist, not class-struggle lines. She also differentiated herself from the suffragist movement: in her view, improving women’s rights to their own reproduction increased the quality of their lives and was a more urgent concern than the right to vote.

Sanger began writing columns entitled “What Every Mother Should Know” and “What Every Woman Should Know” that were frank in their discussions of sexuality and reproduction. According to prevailing laws, however, she was skirting the bounds of legality, violating the 1873 Comstock Laws that prohibited distribution of birth control information on the grounds of obscenity. During this time she became estranged from William Sanger, although they had three children together.

In 1914 Sanger coined the term “birth control” in her monthly newsletter The Woman Rebel and in late summer was arrested for violating obscenity laws. Unwilling to face the legal process, she fled to Europe and was abroad most of 1915. The children were sent to boarding school and to live with relatives.

Sanger’s Year Abroad

Europe brought her into contact with the neo-Malthusians who warned about the rise in global population to unsustainable levels. She also developed a connection with Havelock Ellis, a well-known writer and public intellectual who advocated greater emotional and sexual freedom for women, asserting that sexuality was a natural and joyful aspect of life – even for women. Sanger was also exposed to nations more accepting of birth control, especially the Netherlands where she was impressed by a women’s clinic she had visited.

During this time, her broken-hearted husband managed to get himself arrested for distributing birth control literature and was given a short jail sentence. Although Margaret was angry that a man had become a martyr for her movement, this event contributed to a greater public awareness and support for the issue of birth control. Later, after it had become clear that Margaret had completely moved on from the marriage, their relationship became more adversarial.

Sanger had left for Europe in relative obscurity and returned a public and controversial figure.

Shortly after her return, however, their daughter died of pneumonia after a short illness. This launched Margaret into a tidal wave of grief and guilt that remained with her throughout her life. Margaret’s involvement with her two sons was sporadic; her work was her priority in life.

46 Amboy Street, Brooklyn New York

Site of first birth control clinic in the US, in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn NY

On October 16, 1916, along with Ethel Byrne (mother of Olive) who had the nursing credentials, the two sisters opened up the first birth control clinic in the United States. Previously fliers had gone out in English, Yiddish, and Italian, reflecting those who lived in that area. 446 women visited their clinic before it was shut down and Byrne and Sanger arrested. After posting bail Sanger attempted to reopen the clinic but again it was closed down.

In early 1917 Byrne and Sanger faced charges. Byrne was sentenced to thirty days, responded by going on a hunger strike like the suffragists in England at the time, was brutally forced fed but was later released on the condition that she desist from performing birth control services.

To Sanger the judge stated that women did not have “the right to copulate with a feeling of security that there would be no resulting conception.” She served her thirty days in better conditions than her sister and later regretted that it was Ethel, not she, who had gone on a hunger strike. Byrne was traumatized, Sanger inspired. The resulting publicity was a gold mine that brought Margaret Sanger into national prominence.

Brownsville and Sanger’s Astrology

I depart from my usual procedure and begin with indicators from the Hellenistic era. Circumambulations are a predictive technique that counts moving positions from the ascensional times of their zodiac sign for the latitude of birth, as if these positions were on the Ascendant. This was the alternative to Ptolemy’s method that became the source of later primary directions.

In the middle of 1912, as Sanger was living and working in New York and part of the leftist community, directed Moon was conjunct natal Sun: this was about this time that her feminist cause became the focus of her life. A year after the opening of the Brownsville clinic and coinciding with her larger public profile, directed Midheaven contacted natal Sun by square.

Decennials are a system whereby major planetary lords change place roughly every ten and a half years, the specific planetary lords change unevenly according to planetary number. This system with some variations is cited by numerous sources in the western tradition from antiquity.

Shortly after William and Margaret Sanger moved to New York City, the major and specific planetary lord was Venus, both the ruler of the Tenth House and also signifying Margaret’s working with women. Early 1913 saw Saturn – cadent and in fall – as her specific ruler. This was the time of her first arrest and her flight to Europe. During the summer of 1915, just before her return to the United States, Mars, her most prominent planet, took over as specific planetary lord, and she was finding her rhythm as a social activist. On October 30, 1916, less than two weeks after the opening of the clinic and her well-publicized arrest, Moon, in her natal First House and with a square from Mars, had become specific lord for the following two years, coinciding with her rise to prominence.

Natal, Secondary Progressions, and Transits at opening of first birth control clinic in October 1916. Click for larger picture

Now leaping into the predictive techniques of the modern era, Sanger’s secondary progressions show a Progressed New Moon, often signifying the beginning of a major life trend, occurring early in 1911, shortly after she arrived in New York. Her work with the impoverished immigrant community coincided with progressed Mercury arriving in Scorpio at the end of thatyear. In 1913 progressed Mercury went into conjunction with progressed Jupiter, coinciding with her columns in leftist publications and then as a stand-alone.

On October 16, 1915, the same day as the clinic opening and signaling a Rubicon-crossing event in Sanger’s life and the life of the national women’s movement, progressed Mercury formed an exact sextile to progressed Uranus. This recharged her natal Mercury-Uranus conjunction, and may signify that this demonstration of civil disobedience was also a stroke of genius.

Sanger long-term and short-term transits are complex and interesting. Her Midheaven degree was strongly impacted at this time.

Jupiter entered Taurus in June 1916 and was conjunct her Midheaven degree in July and then, retrograde, early in October; Jupiter returned to Aries and re-entered Taurus the winter of 1917, just in time for Sanger’s month at the “workhouse”. Joining Jupiter in transit to Sanger’s Midheaven degree was Neptune in Leo, forming a square in late July and a long retrograde station February-May 1917. Saturn in Cancer entered Leo, Sanger’s First House and formed a square to Sanger’s Midheaven degree during the summer of 1917.

The Midheaven indexes one’s relationship to the larger public world: Jupiter makes it larger and gives one prominence, Neptune adds an idealistic or self-sacrificial element, and Saturn, especially moving into the First, can be limiting or focusing or soberly pragmatic.

Triggering the opening of the Brownsville clinic was Mars in Scorpio, exactly square her natal Moon and opposing natal Mars and Pluto. Yes, Sanger was ready for a fight.

The longer-term transits coincided not only with the birth control clinic and its judicial aftermath, resulting in Sanger’s increasing public presence, but, with Saturn joining Jupiter and Neptune, her parting ways with leftist politics of the time. Sanger wanted the support from middle and upper-class women who would be alienated by her former allies and who could make financial and personal contributions.

Beginning in 1917 and lasting through the early 1920’s there was a strong political repression in the United States that coincided with new anti-immigrant politics and an invigorated racism. Sanger side-stepped these minefields by casting birth control as a medical issue and striving for support within the medical community. In 1918 the New York Court of Appeals ruled that doctors could prescribe contraception for medical purposes: this was a victory that Sanger could exploit to make further advances.

Returning to Brownsville and October 1916 is her striking solar return chart for that year. A solar return chart is like a natal chart for a year, beginning at the time when the Sun returns to its natal position by minute and second.

This solar return features Ascendant in Leo that is accompanied by Venus and Neptune. Sometimes this combination is about powerful but illusory romantic leanings or exploits, but I doubt Sanger had much time or energy for those things. Instead it manifested by her being a romantic hero – perhaps a martyr – for a noble cause. This solar return also includes Mars in Scorpio in opposition to Jupiter in Taurus, connecting with Sanger’s natal Midheaven degree: opening the clinic connected with Sanger’s family background and how her background would play itself in the larger world. Moon is in feisty Aries for 1918 but is applying in a square to Saturn: it turned out that she was not happy being a suffering martyr and her route would become more pragmatic and conventional.

The Complex Birth of Planned Parenthood

In 1921 Sanger organized the American Birth Control League with the ambition of providing birth control services through clinics operated by women doctors and social workers; this formula, first tried in Brownsville, would eventually become Planned Parenthood. In 1923, buoyed by the ruling that doctors could give contraceptive counseling, she also organized the Clinical Research Bureau to connect with the medical community.

In 1922 Sanger visited Asia and advocated for birth control internationally, helping to set up a clinic in Shanghai, and visited Japan six times for similar work. Beginning in the 1920’s her focus became global.

1922 also saw Sanger’s second marriage, this time to James Slee, an industrialist. Slee not only contributed to the birth control movement but, after their distribution became legal, became a manufacturer of diaphragms. Slee died in 1922 leaving Sanger financially comfortable for the remainder of her years.

Following a period of infighting within that organization, Sanger resigned from the American Birth Control League and renamed the Clinical Research Bureau the Birth Control Research Bureau (sounds like an astrology organization familiar to many of us). Now there were two rival organizations.

In the early 1930’s Sanger decided to make battle with restrictions on distributing contraceptive material like diaphragms. She ordered one from Japan that was confiscated, she went to court, and in 1936 won a major victory when the Supreme Court ruled in her favor, and in the following year the AMA included contraception as a standard medical intervention. On the heel of these victories, Sanger felt it was time to reduce her role and she moved to Arizona.

In 1939 the two rival organizations finally merged into the Birth Control Federation of America that became Planned Parenthood (over Sanger’s objections – too euphemistic) in 1941. She was their first president and continued in that role until she turned eighty, then she finally retired.

During her final years she was cared for sometimes by Elizabeth Holloway and Olive Byrne who had stayed together since they both lived with William Marston in the 1920’s. Margaret Sanger died in 1966 just before her eighty-eighth birthday.

Eugenics and the “Negro Problem”

Eugenics, a movement popular in the United States in the 1920’s, is the study of and activity toward improving humans through controlling inherited traits through controlling mating. This could have the positive end of creating superior individuals and enhancing positive characteristics but also could move toward eliminating procreation that might give birth to defective individuals.

One easily sees Sanger’s interest here: the proper use of birth control could help minimize births not only of unwanted offspring but those who could be defective in some way. During the 1930’s thirty states had forced sterilization of the “feeble-minded” on the books, and Sanger was one of the voices for restrictions of families with “three generations of imbeciles”. However, she was adamant that racial characteristics were not relevant to such matters and took issue with those who held those beliefs. She also felt that birth control was an individual, not a governmental concern.

To Sanger the “Negro Problem”, was simply that there were too many unwanted pregnancies within black families. There is no indication that Sanger was consciously racist; her interest was in reducing the number of children born from poverty. However, she did once give a talk to a women’s auxiliary of the KKK — it was probably about birth control.

Sanger was aware of the gap in services between blacks and whites and of the distrust black women had for conventional medical services. Responding to a black social worker’s request, Sanger helped found a blacks-only birth control clinic in Harlem, staffed solely by black medical personnel. She advocated hiring black ministers for leadership positions, based on their trustworthiness to black women and to counter the suspicion that Sanger was deliberately trying to reduce the black population. Her attempts to help black women with contraceptive services won praises from black leadership from W.E.B. Dubois and Martin Luther King.

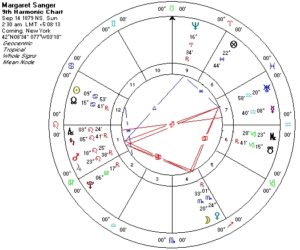

Margaret Sanger’s Ninth

We have seen the importance of Margaret Sanger’s square between Moon and Mars/Pluto and the configuration of Mercury conjunct Uranus, both opposing Jupiter. Sanger’s Ninth Harmonic chart brings together both configurations and helps us understand the relationship between her inner being and her personal expression.

Margaret Sanger’s Ninth Harmonic chart is a thing of beauty, a joy for the astrologer to behold. As you have seen in previous profiles, harmonic charts, based on the arcs between planets and number symbolism, help us determine unique gifts of the individual, if used alongside the regular “radical” birth chart.

Why the Ninth Harmonic? Consider our standard depiction of trines as affiliation and enjoyment, an easy flow between two planets. Multiply that number symbol by itself and you get nine that signifies fulfillment, joy, personal satisfaction at a higher level. One could call it a guiding inspiration.

Looking at Sanger’s Ninth Harmonic chart, you see that the Moon-Mars square that is only separated by a few minutes in the radical chart continue in close square; Pluto, not so close in aspect, is no longer a factor. What company does the Moon-Mars square keep here?

Jupiter joins Mars and Venus that joins Moon! Here are the two “feminine” planets of conciliation and adaptation in square to the yang-energy enterprising duo of Mars and Jupiter. Uranus also makes a strong appearance, opposing Mars/Jupiter and in square to Moon/Venus, adding an attitude of insurgency or unconventionality.

This configuration may sound like an indication of a bomb-throwing rebel, not one who patiently worked with the medical and legal communities, who courted middle-class women and a lot of Rockefeller money.

Here you also see that the Ascendant is with Saturn and Mercury is in opposition. Note that in the radical chart Mercury is conjunct Uranus but in the Ninth Harmonic it is configured with Saturn: Sanger’s cause made her more a rebel than was her preference; Saturn helped increase her determination and focus over a long lifetime of work.

As with Sanger’s chart there are many squares and oppositions, indicating energy and struggle and disharmony, with relatively few “easy” aspects. This is true for her “radical” natal chart and for her Ninth Harmonic chart. Hers was not an easy life but it was a good life.

Sanger’s life and astrology, especially in view of her Ninth Harmonic, reminds me that true happiness is often retrospective – each day presents problems, obstacles, much more challenge than we want, yet looking back we may discover that these were also times of greatest aliveness, of fighting the good fight. Margaret Sanger, who faced a host of difficulties and challenges for days and years, lived a lifetime of joy and fulfillment, something we could all aspire to.

Thank you. Very interesting with lots of food for thought and study